What happens when a part of us believes it has to save the world? What happens when it starts to take over? This piece explores the inner dynamics of messianic intensity through the lens of Internal Family Systems, Heinz Kohut’s work on narcissism, and the transformative potential of stepping back—and seeing that we are not the center of everything, but part of something far more vast and alive.

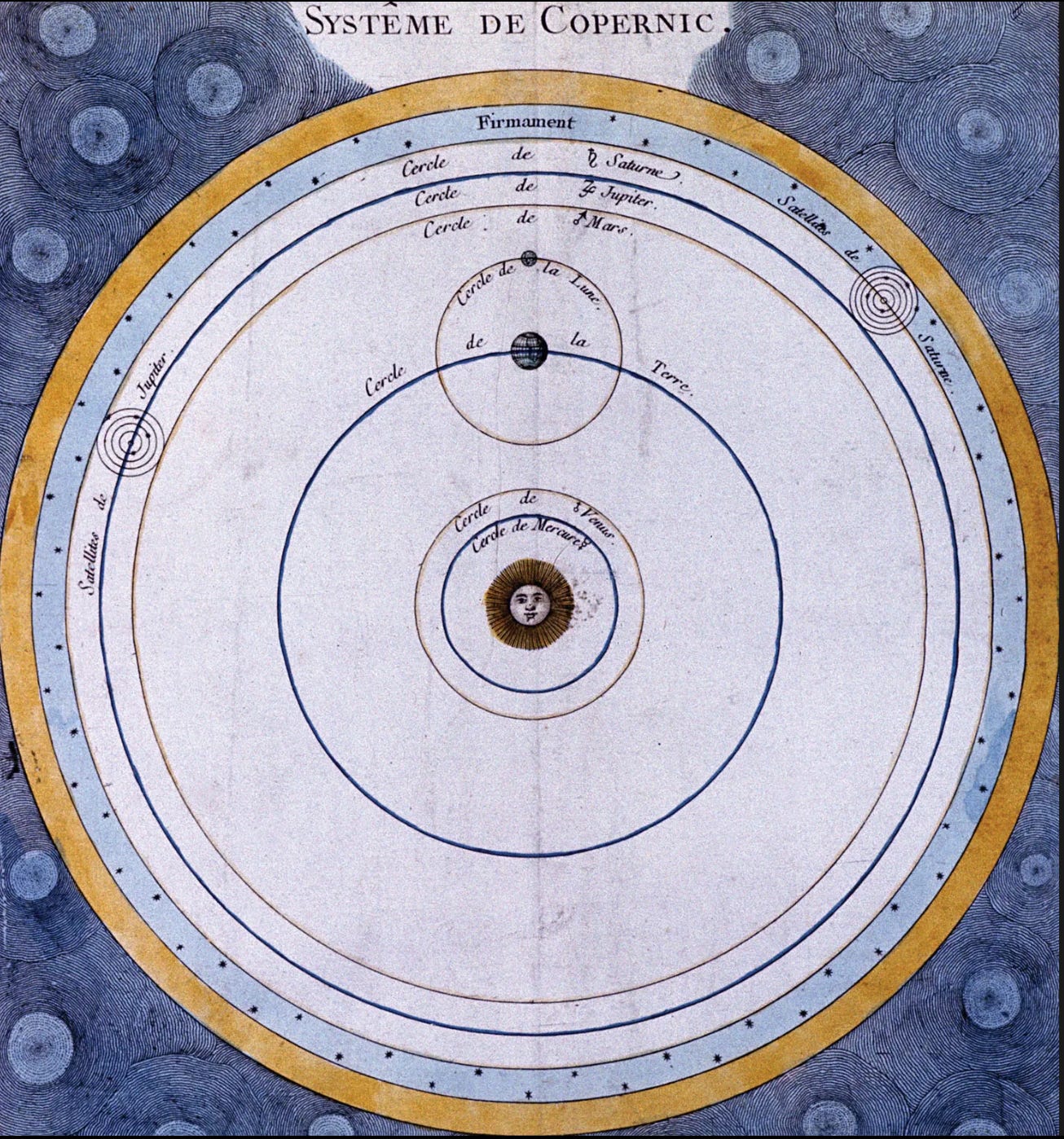

The Copernican Turn: A Shift in the Center of Gravity

There’s a moment in deep emotional and spiritual healing that reminds me of something from the history books. When Copernicus said the Earth wasn’t the center of the universe, it didn’t just change astronomy. It shook how people understood themselves. It was a revolution of perspective—a reorientation away from self-importance and toward relationship.

Something similar happens inside of us, especially in the context of extreme emotional or spiritual experiences.

We all carry different inner voices—some soft, some loud. Some parts try to keep us safe by staying invisible. Others try to hold the whole world together. One of the most powerful I’ve encountered, in myself and in others, is what I think of as the messianic part—a voice that believes it’s uniquely responsible for saving the world.

The Messianic Part

I’ve worked with many people—especially those navigating extreme states or what’s often labeled psychosis—who carry this kind of part. It often appears during spiritual emergencies or identity breakdowns, when familiar support systems have failed. This part might speak with certainty or even divine clarity. It might carry visions. It also often carries a deep loneliness.

At its core, this part is trying to protect. It’s doing its best to create order, to hold meaning, to survive. But it often does so by taking over—by becoming the center of gravity in someone’s inner world.

And when it’s fused with our sense of self—when no other inner voices are available to balance it—it can be overwhelming. Not just for the person experiencing it, but for the people around them.

Heinz Kohut and the Grandiose Self

Long before the language of “parts” became common, psychoanalyst Heinz Kohut was exploring a similar dynamic. He described what he called the grandiose self—a psychological structure that forms when a child doesn’t receive the kind of attention and mirroring they need from their caregivers.

In simple terms: if a child doesn’t feel seen, they may inflate. They may build a powerful self-image in order to survive emotionally. That inflated self believes it must be special, chosen, even godlike—because the alternative is unbearable.

But Kohut was clear: this isn’t narcissism in the way we usually think about it. It’s not arrogance—it’s a wound. It’s a coping strategy. And what that part needs isn’t to be crushed or mocked. It needs to be understood. Held. Mirrored, not to inflate it further, but to let it know it doesn’t have to do it all alone anymore.

This insight aligns with the more contemporary frameworks I use in my work, like Internal Family Systems (IFS)—a therapy model that treats our inner world as a system of parts, each with their own story, role, and relationship to the whole.

Clinical Example: “Jonah”

I once worked with a young man—I’ll call him Jonah—who had experienced multiple psychiatric hospitalizations. He told me he had a mission. That he was chosen. His journals were filled with metaphors, symbols, and messages for humanity. It wasn’t the content of his beliefs that concerned me—it was the weight of them. He was carrying it all alone.

When I asked, gently, if any part of him felt overwhelmed, he paused for a long time.

Then he whispered, “I can’t stop. If I stop, the world collapses.”

That wasn’t all of Jonah speaking—that was a part of him. What I came to understand was that this part had taken over completely. It was blended with his sense of self. There was no space between Jonah and the voice that believed it had to save the world.

We didn’t try to argue with that part or prove it wrong. That would have only deepened its isolation. Instead, we built a relationship with it—slowly, respectfully. Over time, as it began to feel seen and less alone, the intensity softened. The part began to unblend—to step back just enough for Jonah to witness it, rather than be completely identified with it.

And once there was some space, something remarkable happened: that part started to reveal what it was protecting. Beneath the grandiosity was a much younger Jonah—a child who had to play the adult in a chaotic home, who believed that being extraordinary was the only way to be safe, the only way to matter.

As Jonah’s relationship to that part deepened, the messianic energy didn’t disappear—it transformed. It was no longer running the show. It became something else: a visionary presence, not a savior. An advisor, not a dictator.

That stepping back—that act of unblending—changed everything. It was Jonah’s Copernican Turn: the moment when he stopped orbiting around that part and began to re-center himself in relationship to the whole.

Cultural Parallels: Trump, Musk, and the Unexamined Center

When I look at some of the loudest figures in our culture—politicians, tech moguls, influencers—I often see what I would describe as messianic parts that never had the chance to step back. Inflated self-states that have never unblended. Charisma fused with unresolved wounds. Power wielded without reflection.

Figures like Donald Trump or Elon Musk don’t just hold influence—they shape reality around themselves. Their personas demand loyalty, command attention, and rewrite the rules to maintain their centrality. In IFS terms, these are protector parts that have taken over completely. There’s no visible relationship to the rest of the system—no humility, no curiosity, no access to exiled parts that might hold grief, shame, or vulnerability.

And because these parts have so much cultural amplification, their internal dynamics become externalized. It’s not just personal—it becomes social. We end up living inside a kind of collective psychosis, where complexity collapses into spectacle, and everything revolves around one voice, one ego, one algorithm. The result is imbalance on a massive scale: emotionally, politically, ecologically.

The rise of authoritarianism, the glorification of the “visionary founder,” even the way social media rewards outrage and certainty over nuance—all of it echoes this same psychological pattern. We are living in a time of mass blending.

But here’s the thing: Jonah was willing to turn. He was willing to question the story that everything depended on him. He allowed space for relationship, for other parts of himself to come forward, for uncertainty to be part of the picture. That’s the real difference.

And if there’s hope for us culturally, it lies in that capacity—the willingness to step back, to unblend, to become part of something larger than the self we’ve been clinging to.

After the Turn: The Gift in the Fire

Here’s the paradox: the messianic part often carries something valuable. Passion. Vision. Urgency. A longing for transformation.

But it’s been alone too long.

When we create space around it—when we listen without letting it take over—it can shift. It doesn’t have to vanish. It just has to find its right place in the system.

Not the center. But part of the constellation.

When that happens, people don’t lose their fire. They learn how to tend it. They learn how to lead from a deeper place—not because they’re extraordinary, but because they’re in relationship.

Final Thoughts

There’s nothing wrong with having a part of you that wants to change the world. But it doesn’t have to do it alone.

Healing isn’t about shutting those parts down. It’s about unblending from them. Creating enough space for connection, for curiosity, for other perspectives to enter the room.

And in that space—when the inner gravity shifts, when the messiah becomes a guide, when the fire becomes shared—that’s when something truly new becomes possible.

That’s when we stop spinning alone, and start finding our place among the stars.

Find me in my private/public practice:

beautiful and well said

Powerfully beautifully said, my friend!