The Kindling Effect

“The schizophrenic drowns in the same waters in which the mystic swims with delight.”

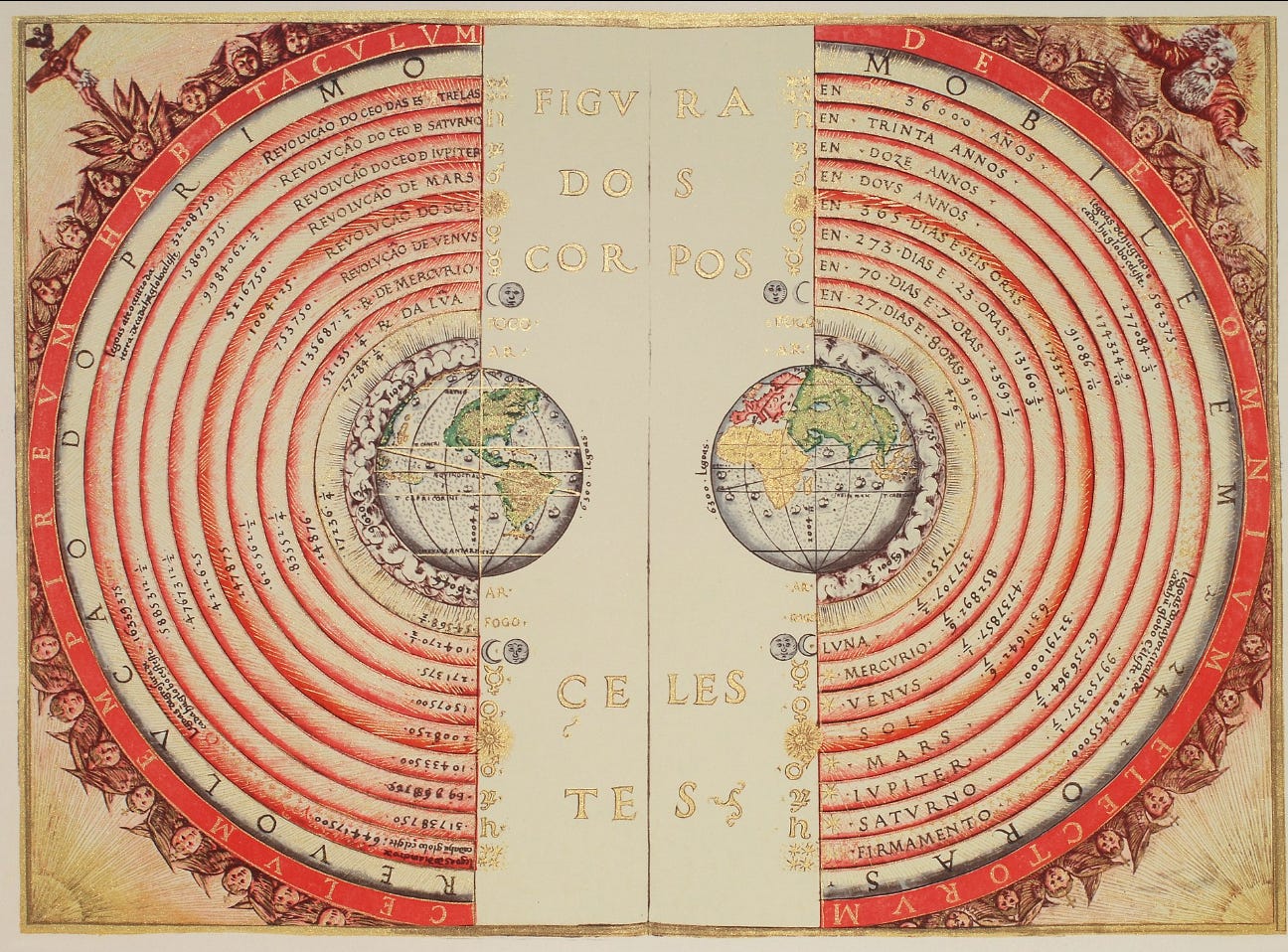

I still remember how the doctors explained it to my mother when I was a teenager. “If he’s not medicated,” they said, “he’ll keep having more breakdowns, like setting off fires in his brain.” Each psychotic episode would supposedly burn deeper pathways, making the next one harder to control. They called it ‘The Kindling Effect’—a terrifying, seemingly scientific way to describe the fate of my mind if I didn’t take their medicine. The daily Haldol and the Depakote in the hospital were supposed to keep that fire at bay, building walls between me and the parts of myself that felt too dangerous, too out of control.

But here’s the thing about walls—they’re never permanent. They crack, they leak, and sometimes, the things you’re trying to block out sneak through. It’s not as simple as putting out the fire; it’s about learning to navigate its heat without letting it consume you. Even though the drugs dampened the flames, the dangerous, visionary parts of me still found their way back. My adult life has been an ongoing negotiation between safety and freedom, navigating the different internal worlds I call home.

The Dilemma of Control vs. Authenticity

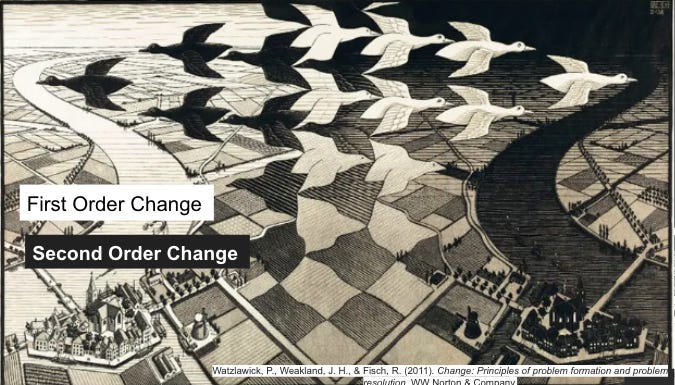

In my teenage years, I didn’t understand the full gravity of what the doctors were saying. All I knew was that they were offering me two paths: control through medication or a future where my mind spiraled out of control, consumed by an unpredictable fire. The fear of losing myself to those flames was real, but so was the fear of losing myself to the drugs. The walls they built around the dangerous parts of me didn’t just block out the heat—they also blocked out parts of my creative spirit, the visionary energy that felt like both a gift and a curse.

As I got older, I started questioning whether this constant need to contain the fire was really about healing or whether it was about making me conform. The same flames that psychiatry saw as a threat, other traditions might have seen as a transformative force—an initiation into deeper understanding, a connection to something larger than myself. But for me it wasn’t so simple as just rejecting psychiatry, as much as I didn’t trust their medical paradigm I found the medications helpful in staying grounded and focused.

I ended up choosing a different path. After my third inpatient hospitalization when I was 26, I decided to take the drugs, specifically lithium carbonate. It allowed me to maintain a connection to my creative side, but it also kept me from getting too high or too low. “Like having lead weights on my wings,” I would tell friends. “I can still fly, but I don’t have to worry about melting my wings and drowning in the ocean”—a reference to the myth of Icarus. Lithium became an anchor that prevented me from soaring too close to the sun, while still enabling me to exist within both creative and grounded realities. It allowed me the stability to build a community around me with a vision of transforming the whole way we think about mental health and illness.

But that decision came with a price. Whether I understood the implications or not, by choosing lithium and its stabilizing effects, I was also choosing to wall off the part of me that carried the fire—the part that had once driven me toward grand visions and intense emotional highs. In my quest for stability, I effectively exiled a vital part of myself, the one that held both danger and brilliance. Over time, this created a quiet tension inside me. I was able to move through life with more stability, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that I had left something important behind, something I wasn’t ready to fully abandon.

That part—the one I kept walled off—wasn’t just about madness or chaos. It was the part that connected me to a deeper understanding of the world, a part that might’ve been seen as visionary in another context. But in this context, in this culture, it was pathologized, medicated, and hidden away for the sake of normalcy. And while I functioned, succeeded, and built a life, the cost was always there—a quieter life, a more manageable existence, but with the ever-present knowledge that the fire I had worked so hard to contain was always waiting, just on the other side of those walls.

I’ve been taking lithium carbonate for 23 years now, and it’s allowed me to accomplish things I never imagined possible for someone as sensitive and reactive as I am. The medication didn’t extinguish the fire within me, but it has helped manage it. It has allowed me to build an unorthodox career, maintain long term relationships, and stay tethered to a version of stability that I couldn’t have imagined when I was a young man. But there’s always been unanswered questions: how much of the fire, the visionary energy, was dampened in the process? At what cost did this stability come? What would my life be like if I had been able to integrate my prophetic 18 year old visions rather than just drug them away?

Dreaming of a Different Path

“The schizophrenic drowns in the same waters in which the mystic swims with delight.”

The election of Donald Trump in 2016 exposed a terrifying fault line in how we understand rationality itself. Our cultural narratives about reason and stability—about who is “sane” and who is not—appear to be collapsing into absurdity. Millions of people looked at Trump, a chaotic, narcissistic figure riddled with erratic behavior, and saw a kind of savior, a mythic father figure who would deliver them from despair. That so many projected such archetypal significance onto someone so clearly unstable speaks volumes about the state of our collective psyche. And yet, in a society where teenagers experiencing psychosis are funneled into first-episode psychosis (FEP) programs and labeled as “mentally ill,” Trump and others like Elon Musk wield immense power without ever being subject to such scrutiny.

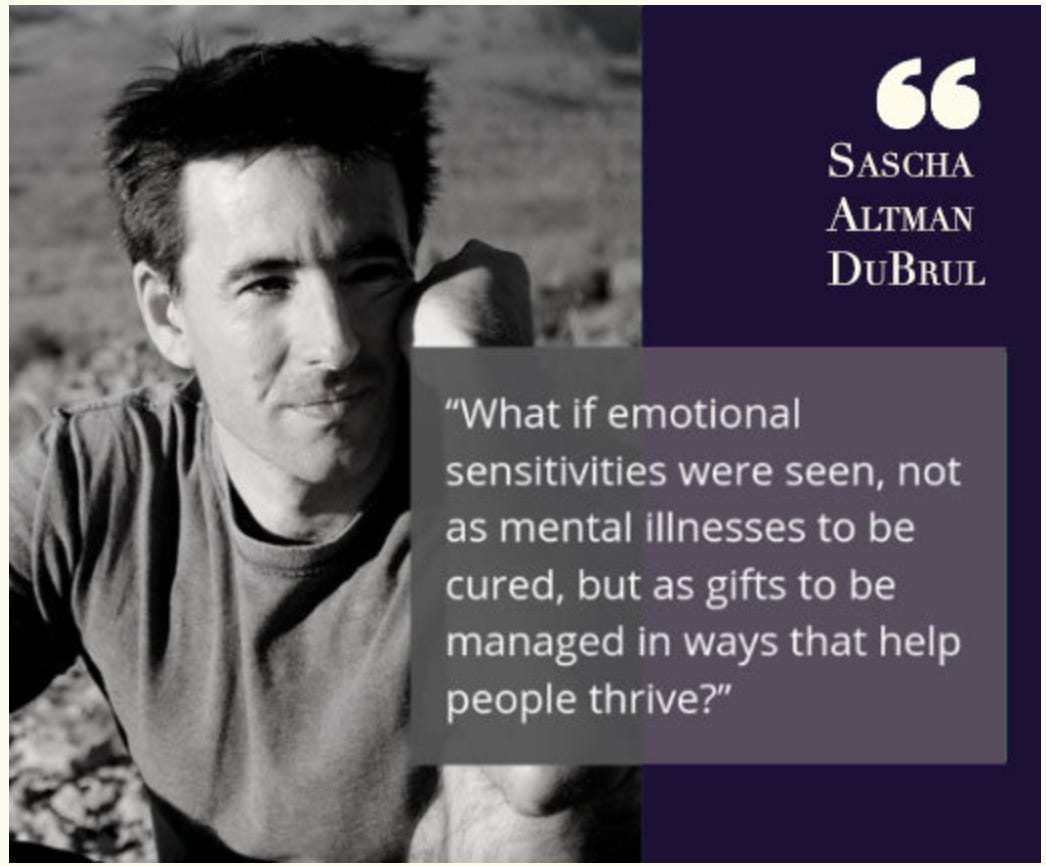

I worked in an FEP program at the New York State Psychiatric Institute for three years. I saw firsthand the immense pressure to pathologize and “fix” those who step outside the bounds of consensus reality. And yet, I’ve often wondered: What if we’re approaching this all wrong? What if what we call “psychosis” is less a disorder and more a reflection of deeper mythic truths—an attempt by the psyche to reconcile or transform in the midst of crisis?

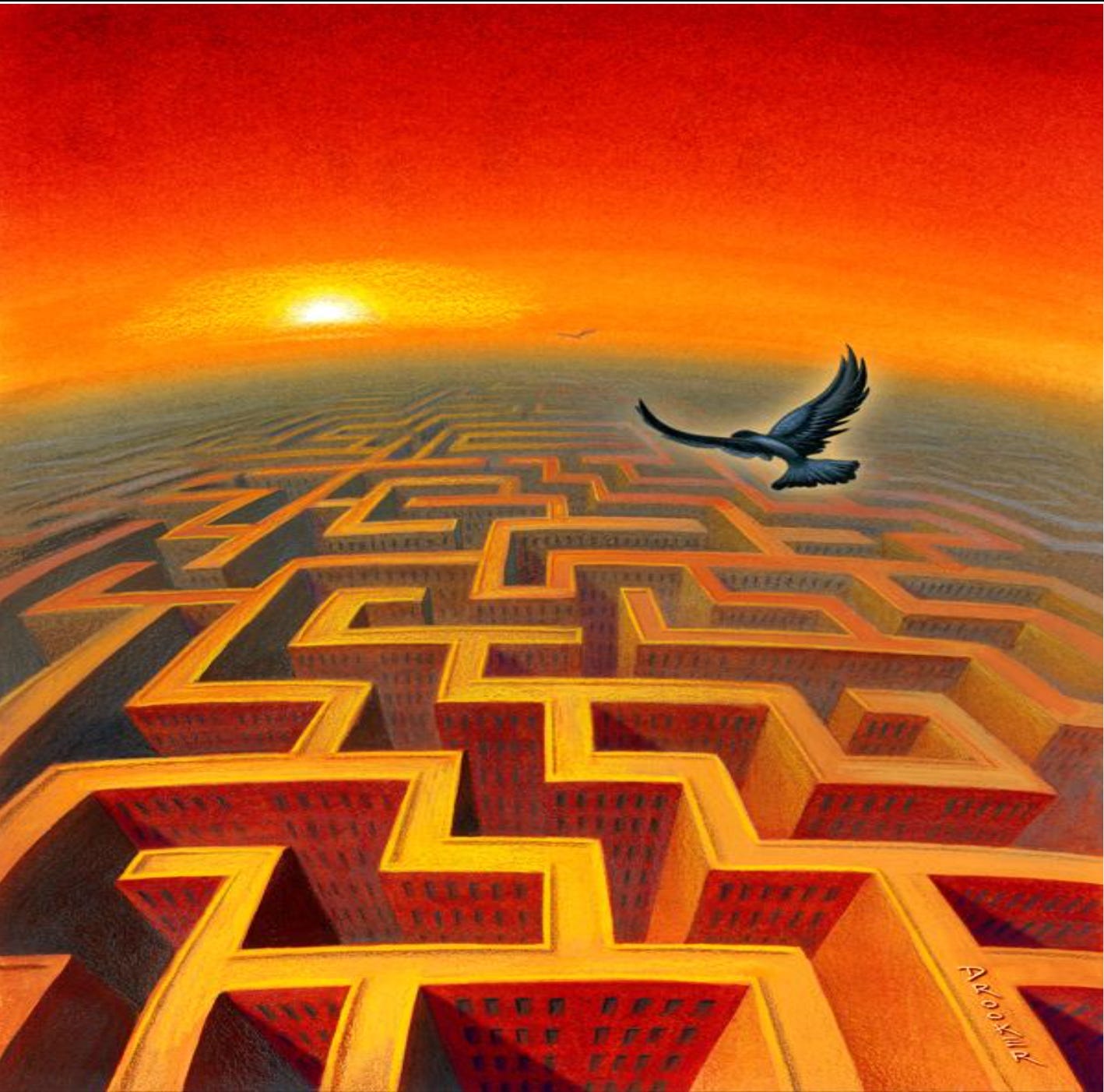

I think about John Weir Perry’s Diabasis House, Loren Mosher’s Soteria House, and R.D. Laing’s Kingsley Hall—sanctuaries of the 1960s and 70s where psychosis was seen as a profound journey. Perry described it as the psyche’s attempt to dissolve outdated patterns and birth a renewed self. The mythic imagery that arises during psychosis—battles between good and evil, messianic visions, death and resurrection—isn’t random; it’s the language of the unconscious, trying to reorganize and heal itself. But instead of helping people through this process, modern biological psychiatry labels it as meaningless pathology, medicates it into silence, and interrupts the transformation before it can complete its arc.

Joseph Campbell once said, “The schizophrenic drowns in the same waters in which the mystic swims with delight.” The difference is in the support and context. Perry’s work showed that when people experiencing psychosis were supported in environments free of judgment and overmedication, they often emerged transformed, usually within 40 days. Without that support, the process is suspended, leaving many stuck in an unresolved state. Jung understood this too: when the ego is overwhelmed by archetypal imagery, it feels like a terrifying descent into chaos. But this descent has a purpose—it’s a chance for deep integration, a realignment with the larger Self.

I remember the first time I felt my mind break apart. I was 18, and I believed I was at the center of an epic cosmic battle. It was terrifying and disorienting, but looking back, I see it as a trial by fire. The old structures of who I thought I was—how I fit into the world—were being burned away to make space for something new. What might have been possible if, instead of being locked up and sedated, I’d been guided through the fire by people who understood its deeper purpose?

Meanwhile, as a society, we’ve handed the reins of power to figures like Trump and Musk—men whose behavior would, under other circumstances, lead to psychiatric diagnoses rather than cult-like adoration. Why are some expressions of madness criminalized or medicalized, while others are idolized? This double standard reveals the hypocrisy at the heart of our systems: madness is feared and controlled when it emerges in the powerless, but it’s celebrated—or at least tolerated—when it manifests in those who dominate our collective imagination.

This isn’t just a question of individual healing but of societal transformation. If we saw psychosis as a journey of renewal rather than a pathology, how would our systems change? What if we created sanctuaries where people could explore these mythic realms with compassion, humility, and curiosity? Perry’s vision of psychosis as a renewal process challenges us to rethink our fear of madness. It invites us to see the mad ones not as broken but as holders of wisdom, offering keys to understanding the depths of our fractured reality.

The fire of psychosis is both dangerous and sacred. It can destroy, but it can also illuminate, revealing truths we’ve suppressed or forgotten. To embrace it is to step into a space of transformation—one that demands courage, trust, and support. As I reflect on my own journey, and on the systems I’ve worked within, I see this fire not as something to extinguish but as something to honor. If we can learn to hold it with care, it might not just transform individuals but offer a path toward healing the deep fractures in our world.

How do we flip the current script?

public/private practice:

Beautifully written.