Not Broken, Not Sick: A Rebellion Against the Anosognosia Frame

A Systems and IFS-Based Critique of the LEAP Model and the Medicalization of Resistance

Xavier Amador’s model of “anosognosia”—the clinical term for when someone is unaware of their illness—has become a cornerstone of how psychiatry explains why people diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder might refuse treatment. Promoted through the Treatment Advocacy Center and formalized in his LEAP (Listen–Empathize–Agree–Partner) method, Amador’s framework has been widely adopted in psychiatric practice, family education, and even law enforcement training.

But there’s a profound problem with this worldview: it casts resistance as malfunction. It erases the possibility that noncompliance might be a response to trauma, a form of relational protest, or an act of survival. Instead of seeing dissent as meaningful or contextual, it reframes it as a symptom of a broken brain. This framing is not just misguided—it’s dangerous. In a time when conformity is increasingly rewarded and dissent punished, reducing resistance to a neurological defect serves the interests of social control more than healing. It medicalizes disagreement and clears a path for coercion in the name of care.

I’ve lived inside these questions. Diagnosed in my late teens with what would now be called a serious mental illness, I was once the person being told I lacked insight—when in fact I was fighting for my life, trying to protect something essential in myself. These days, I work with many people who struggle with what gets called SMI. They are not broken. They are often brilliant, wounded, and resisting something that never made sense to them in the first place.

The LEAP framework has real consequences. It trains clinicians to pathologize resistance. It encourages family members to override autonomy. And it fuels the use of forced treatment in the name of neurological compassion. What Amador’s model lacks—what it actively avoids—is any form of systems thinking, any awareness of relational dynamics, and any recognition of internal multiplicity. It silences the wisdom embedded in parts, in context, and in survival.

Let’s break down why this model is so problematic.

1. IFS: There’s No Such Thing as a Unified Self to Be “Broken”

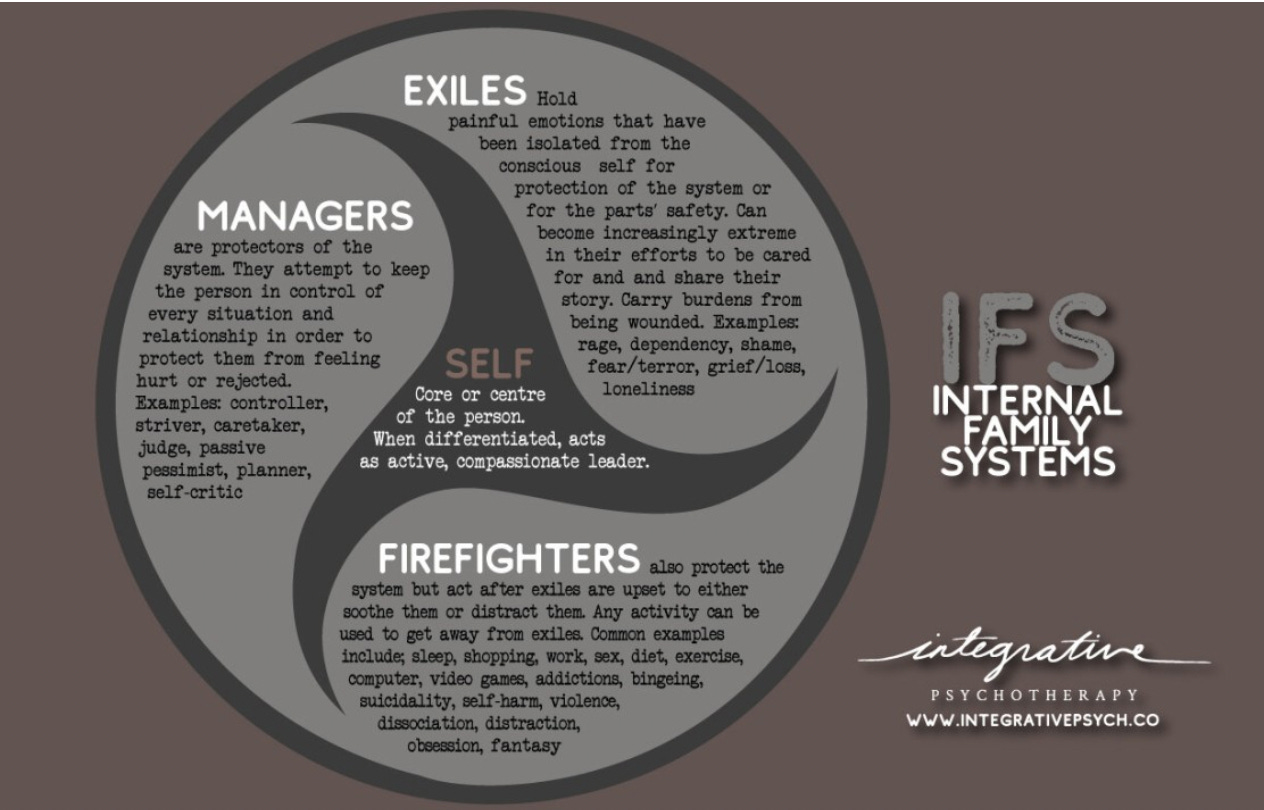

Amador writes as if every person has a singular, fixed self-concept that gets “stranded in time” when mental illness strikes. He positions “insight” as a binary: you either believe the doctors or you are sick. But from an Internal Family Systems (IFS) perspective, what he describes as “lack of insight” is more accurately understood as internal conflict between parts.

The person who says “I’m fine, I don’t need medication” is not necessarily delusional or neurologically damaged. They may be speaking from a protector part—one that’s protecting against the shame, terror, or loss that would come from identifying as “mentally ill.” They may have a burdened exile holding memories of betrayal or coercion by the mental health system. They may have a firefighter part that actively pushes away any association with a label that’s been used to justify control and force.

To label this internal system as “broken” is not just inaccurate—it’s dehumanizing. It collapses complexity into pathology.

2. Systems Thinking: People Resist Because Systems Hurt

Amador writes as if the only relevant “system” is the nervous system. But anyone who has worked in real-world psychiatric contexts knows that families, institutions, and social power structures play massive roles in shaping someone’s relationship to treatment.

Take Matt, the fictionalized patient described in the article that inspired me to write this article. The clinicians gathered around him see a “defensive,” “stubborn,” “prideful” man. No one asks: What happened to Matt? What was done to him? Who gets to define his reality? What kind of system is he being asked to reenter, and does it feel safe?

In systems thinking, we would ask: how are multiple systems—family, hospital, economic precarity, racism, ableism—interacting to shape Matt’s experience? Instead, Amador’s team signs the discharge papers and predicts relapse, not as a failure of relationship or system design, but as a neurological inevitability.

This is the medical model’s sleight of hand: it turns relational wounds into individual defects.

3. The “Insight” Trap: Whose Knowledge Counts?

Central to Amador’s argument is the idea that insight = agreement with a psychiatric diagnosis. This is epistemic colonialism: your experience only counts as “valid” if it matches the DSM.

He dismisses cultural explanations (e.g., “I’m possessed,” “I have a nervous problem”) as quaint and unscientific. He mocks the possibility that someone might prefer their visionary state to what psychiatrists label wellness. He never seriously entertains that treatment refusal might be wise—an act of spiritual or political discernment, not confusion.

Insight, in his framework, is not self-knowledge. It is conformity. Anything else is neurologically broken.

Bridging the Gap: Toward Narrative and Relational Insight

To be clear, I don’t believe that insight is a meaningless concept. As Awais Aftab rightly points out, insight can’t simply be dismissed as a psychiatric tool of control. There are real human experiences—what he calls “ruptures in shared reality”—that deserve to be named, understood, and held with care. I’ve seen this up close. I’ve sat with people in the throes of expansive or terrifying states who later say, “I lost my mind—and I needed help finding my way back.” That too is insight, but it doesn’t look like conformity. It looks like narrative. It looks like healing.

The problem isn’t the recognition of these ruptures—it’s how they get framed and who holds the power to interpret them. Aftab describes a judge asking a man about his involvement with the CIA to demonstrate delusion. But what if that story, however implausible, is doing something vital for that person’s psyche? What if our job isn’t to confirm or deny its factuality, but to ask what part of them is speaking, and what it’s trying to protect? We need a new language of insight—one that includes narrative, multiplicity, culture, trauma, and relational safety. Otherwise, we’ll keep mistaking spiritual emergencies for broken brains and survival strategies for symptoms.

5. The Double Bind of Care: “You Must Be Sick If You Don’t Want Help”

Amador’s model sets up a disturbing double bind. If someone agrees to treatment, their compliance confirms the diagnosis. If they resist, it’s not a sign of autonomy or disagreement—it’s proof of anosognosia.

This is eerily similar to patterns seen in coercive relationships. “You only say no because you don’t know what’s good for you.” It’s also a rhetorical trick that removes all agency from the person being labeled. You cannot win. The very act of saying, “I don’t need help,” becomes the reason you are said to need help.

It’s troubling that this logic is not only mainstream but is shaping legislation around involuntary treatment.

Narrative Insight

In contrast to the LEAP model’s rigid dichotomy between “insightful” and “anosognosic” individuals, emerging research on narrative insight offers a more nuanced and respectful framework. A 2008 study by Roe, Yanos, and others entitled Call It a Monster for Lack of Anything Else introduced the idea of narrative insight — recognizing that people experiencing psychosis often hold complex, evolving beliefs about their experiences that may not align with clinical labels but still reflect deep self-awareness. Instead of demanding conformity to psychiatric language, this model makes space for spiritual, metaphorical, or culturally rooted understandings of mental suffering. Importantly, it highlights that rejecting a label like “schizophrenia” doesn’t equate to denial or delusion — it may be a form of meaning-making or resistance to pathologizing narratives. The LEAP model’s insistence on agreement as the basis for connection flattens these subtleties and risks further alienating the very people it seeks to engage.

6. A Trauma-Informed Lens: What’s Missing Entirely

Amador’s decades of writing contain no real reckoning with trauma. There is no mention of how psychiatric hospitalization, medication, or family systems themselves may create or exacerbate trauma. There is no mention of racialized violence, poverty, gender-based oppression, or intergenerational wounds.

In IFS language, his entire framework is protector-heavy. It seeks compliance through strategy, not connection. There is no unburdening, no Self-energy, no invitation to healing. Just an insistence: take your meds. Accept your label. Or else.

7. Oliver Sacks and the Beauty of Excess

Oliver Sacks, in The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, reminds us that not all neurological phenomena are deficits—some are excesses. He writes of states where the mind overflows: too much energy, too much perception, too much meaning. These excesses can be disorienting, even dangerous—but they are not inherently pathological. In fact, Sacks suggests they may carry poetic or spiritual significance, especially when we approach them with curiosity rather than fear.

This is where Amador’s model fails most profoundly: it cannot hold excess. It flattens complexity into illness, treating expansive, often creative states as malfunctions to be corrected. But what if, as Sacks might argue, some of these “malfunctions” are actually attempts at healing, coherence, or resistance? What if the person is not broken—but overflowing?

8. The Political Stakes: Whose Framework Gets Funded?

It’s enraging how much power this model has. Amador gets citations in the DSM. His language is used in state policy. Family members are trained to “LEAP” their loved ones into submission.

Meanwhile, approaches like Open Dialogue, peer respite, transformative mutual aid practices, and even basic harm reduction are underfunded, under-researched, and often pushed to the shadows.

But we’re not going away. We are building something different—not out of ideology, but out of necessity and love. We are the ones actually listening, empathizing, and partnering—not to manipulate, but to witness, respect, and co-create.

Conclusion: We Don’t Need More Compliance. We Need More Complexity.

Amador’s model is a tidy solution to a mess that was never meant to be tidy. It offers families a comforting illusion of control. It offers systems a way to justify coercion. But it fails utterly to meet people where they are, to understand the logic of their inner systems, or to honor the wisdom that lives in resistance.

What we need is a new paradigm—one that sees madness not as a defect but as a signpost; one that treats people not as broken brains but as whole systems in pain and transition. One that listens not just with strategies, but with presence.

If you're working with me—or reading this—chances are you or someone you love doesn’t subscribe to the LEAP model. You know there’s something missing in that script. And you’re not alone.

We need new family networks that can stand alongside us—not to fix us, but to walk with us. Networks that offer listening instead of labeling, relationship instead of diagnosis, support instead of coercion. We don’t need to destroy NAMI—we just need to grow something better. Something kinder. Something rooted in systems thinking, inner multiplicity, and love.

We don’t need to LEAP. We need to stop, slow down, and listen for real.

Find me in my public/private practice:

Cringing the whole time I'm reading this and the Amador article you link to. Clearly Amador is lacking insight into his dysfunctional perspective. Hm. His resistance confirms my diagnosis of coercive tidiness obsession disorder, which includes lack of self-insight as one of its symptoms.

This is how it plays out on the ground: https://www.publicsource.org/allegheny-county-assisted-outpatient-treatment-aot-involuntary-302/?fbclid=IwY2xjawKQqERleHRuA2FlbQIxMQBicmlkETE0aGpLYWJRYjBNOUtKaThwAR5BA5NWS6ED00SkvPnWzjFBUS6f3IYMjwndYH_9ANCqJn8pqHAaWCVHkfkVfQ_aem_VKAgdHUvy60qpGMSiGv4mw